Urban Planning Dream or Nightmare?

Creada el 27 de Enero de 2014 a las 11:39 por jorgerodarProyecto: Urban Games 2013

Tema: Recursos

Coordinadores:

abarca

dacama

Valoración general

0/5 (0 votaciones)Valoración de coordinadores

0/5 (0 votaciones)Descripción

EntradaBlog

Entrada de Blog

In Best-Laid Plans, the Antiplanner argues that cities are too complicated to plan, so anyone who tries to plan them ends up following fads and focusing on one or two goals to the near-exclusion of all else. The current fad is to reduce per capita driving by increasing density and spending money on rail transit.

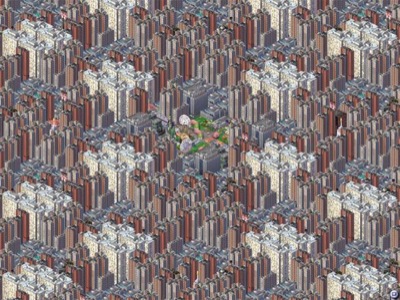

The logical end product of such narrow-minded planning is illustrated by a SimCity constructed by Vincent Ocasla, an architecture student from the Philippines. His goal was to build the densest possible SimCity, and the result is a landscape that is almost entirely covered by high-rise towers used for both residences and work. There are no streets and residents travel either on foot or by subway. There is little need for travel, however, as most residents live in the same tower in which they work.

Magnasanti, as Ocasla calls his creation, does have a few down sides. Dirty industry allows for higher densities than clean industry, so the air is polluted and the average life span in the city is only 50. A strong police force keeps residents from rebelling. As Ocasla says, residents have been “dumbed down, sickened with poor health, enslaved and mind-controlled just enough to keep this system going.” As another blogger points out, Magnasanti “teaches us the pinnacle of urban planning is a totalitarian death state.”

Naturally, urban planners will emphatically deny that they want to build magnasantis. But Ocasla’s creation raises important questions: if driving is so bad that we have to reduce it, where do we draw the line? If single-family homes are bad because they waste land and encourage people to drive too much, why allow people to live in single-family homes at all?

Planners respond that they just want to provide people with choices. But Portland planners (and planning-oriented politicians) are letting roadway bridges fall down even as they spend$1.5 billion or more on a light-rail line to a community that has repeatedly voted against light rail. (Portland planners even claim to have “found” $20 million in savings from the unfunded Sellwood Bridge project to spend on the light rail.)

Meanwhile, planners are perfectly happy for people to live in single-family homes as long as they can afford to buy them. But the same planners see nothing wrong with using urban-growth boundaries and onerous permitting processes in California to make such homes cost five times what they ought to cost.

There also seems to be no limit to what many transportation planners and rail advocates are willing to let other people pay for high-speed rail. Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood has vowed that nothing will stop the Milwaukee-to-Madison moderate-speed train (which initially at least will be slower than the existing bus), even though it will require $130 in subsidies per rider and compete against an unsubsidized bus whose average fare is less than $20. Just how ridiculously expensive does high-speed rail have to be before transportation planners say, “this makes no sense”? Instead, it seems most would support anything, no matter what the cost, if it would get even one person out of his or her car.

Not only are urban planners across the country overly focused on one objective, it is the wrong objective: because alternatives to driving are either slower or more expensive or both, reducing driving unequivocally means reducing mobility, and reducing mobility means reducing economic productivity (not to mention recreation, social, and other opportunities). Magnasanti shows, says Ocasla, “that by only focusing on one objective, one may end up neglecting, or resorting to sacrificing, other important elements.” The Antiplanner hopes that planners and planning advocates learn this lesson soon.

Comentarios

Aún no hay comentarios para esta entrada. ¡Sé el primero!

Accede o regístrate para comentar y puntuar la entrada.